First, I’d like to give you a little background about how I learned to leyn as an adult, more than 20 years ago. Avrom and I moved to North Carolina, and not knowing anyone, we started going to Beth El, a small Conservative congregation, figuring it was a good way to meet other people.

First, I’d like to give you a little background about how I learned to leyn as an adult, more than 20 years ago. Avrom and I moved to North Carolina, and not knowing anyone, we started going to Beth El, a small Conservative congregation, figuring it was a good way to meet other people.

It was a small shul, largely run by the laity, who led all of the davening and did most of the leyning. Once we started coming weekly, the leadership figured us as easy marks for “doing stuff” and asked if we wanted to learn to read Torah. And although I had always been told I could not sing in music class in elementary school – and figured this was true because my dad was completely tone deaf – Jon Wahl, a Beth El member assured me that singing was not the key to leyning (although it probably helps) and that I could probably manage to learn how. Anyway, it turned out I had, for want of a better word, a knack for putting the tune to the words when it came to Torah.

One of the first things I learned to leyn, after our trope class ended and “graduated” by reading the Torah on Shavuot, was the story of Potiphar’s wife, which I read in today’s Parsha, Veyeshev. In the story, Potiphar’s wife attempts to seduce Joseph, who turns her down, and instead of ending up in her bed, ends up in prison. The first time I leyned this, I was a little worried. The story contained one of only four shalshelets in the Torah. A shalshelet is the odd trope that you heard me leyn this morning that sounds like this:

So you can imagine, for someone who was always told that she could not sing and had to stand in the back of the chorus in elementary school with the boys because her voice was too low, this was a little daunting.

For those of you who don’t leyn Torah or who learned their bar or bat mitzvah parsha from a tape their cantor made – as was the custom when I was that age – you may not know the trope marks, or ta’amim. I never learned them, or even the basic tune from mimicking a recording. Because I had been told so many times that I could not sing, I refused to chant when I became a bat mitzvah. Just the idea that I would do this, which to me was singing by any other name, in public was so profoundly embarrassing, that I simply refused. It wasn’t the only thing I was obstinate about regarding my bat mitzvah, but the others would fill enough time for another d’var.

Learning to chant, however, as an adult and by choice has been very gratifying. It has helped me learn the text better on meager Hebrew skills and gives me a connection to it that is hard to describe. I feel tied to something both ancient and ongoing when I read for you. The idea that men thousands of years ago sang these same stories to this tune to a crowd of listeners is a little mind-boggling.

But back to the shalshelet, and its twists. It is just one of about 28 trope. I say about because some only become specific sounds in combination with others. There are two tropes (yereach ben yamo and karney phara) that appear only once each in the Torah and they are all in the same sentence!

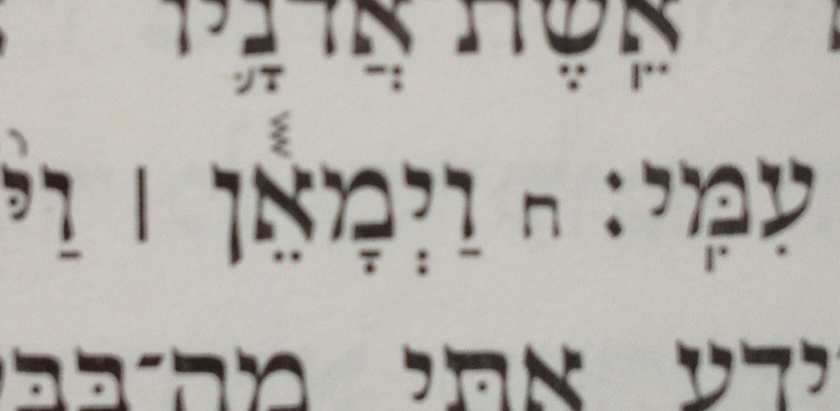

The trope marks appear as kings or servants, above or below the words. They look the same no matter what you are reading, Torah, haftarah, Megillah Esther, Aicha, Ruth or Shir Ha’shirim. But as you know, just from hearing those different books, the song of the ta’amim is different for each of those books. This is more a system of sounds than it is notes, and the first song I learned was the one for Torah. In the case of the shalshelet, it goes up and down the scale three times, and is supposed to contain 30 notes within it. I’ve never counted, so I’m not sure I have hit that many ever. The word translates as “chain” in English and the cantillation mark looks a bit squiggly and chain-like. If you ask me, it looks a lot like it sounds. It is among the rarest trope in the Torah and it is helpful to remember here that the stories of the Torah in all likelihood began as an oral tradition, passed down from one storyteller to another. The cantillation is a way to help remember the words, give pause and phrasing to the sentences and enhance the storytelling. If you just stand there and intone, like I insisted for my bat mitzvah, it really is very boring. Of the four shalshelets in the Torah, three appear in Bereshit alone.

Shalshelet makes its first appearance in Parsha Va-yera, Bereshit 19:16 on the word “Vyitmahmah,” which “Etz Hayim” translates as “still he delayed.” Here the visiting angels have warned Lot away from Sodom and he cannot make up his mind what to do, “should I stay, or should I go?”

The next shalshelet appears in Parsha Chaya Sara, Bereshit 24:12. Eliezer, sent to find a bride for Isaac, pauses and prays for assistance in the task. “And he said,” or “Vyomar” is given the trope. Here it has been interpreted to indicate hesitation or conflict before this daunting task. “What if I screw up and bring back the wrong girl?”

The last time that a shalshelet makes an appearance is in the book of Vayikra, 8:23. The trope lands on “Vyishchat,” describing Moses about to slaughter or shecht andanimal, after which Moses anoints Aaron and sons as priests with the blood. At least one interpretation says that Moshe hesitated because he coveted the position himself. Another explanation is that the trope marks Moses final act of ritual slaughter and each rung of the shalshelet has meaning: “The first run of the shalshelet suggests his anguish; the second his resolve and forbearance; and the third, the greatness of his humility and self0sacrifice.” (Mois A. Navon)

In each case, the shalshelet appears on the first word in the pasuk, and serves as a sort of auditory neon sign: Pay attention! Something big is about to happen in the story. A shalshelet, in short, is a game changer.

In today’s parsha, the trope appears in verse 8, on the word, “Vyimaein,” or “and he refused.” Again, it is the first word of the pasuk and it heralds something significant will follow. Since I’ve had nearly two decades of leyning this story – there were some off years when there was a bar or bat mitzvah who leyned it instead (and I know who you are) – I’ve had a lot of time to think about this trope, this word, the relationship to the parsha, and what it means.

For me the story of Joseph turns on this refusal. It marks the point where Joseph turns from being a spoiled brat, to becoming the man who will save not only his adopted country, but also his own people, and ultimately down the road be big enough to reconcile with a family that sold him into slavery. In short, Joseph is able to transform from an arrogant youth who dreams that his family will bow to him; into the commanding person who will ultimately be bowed to.

The trope is sometimes taken to mean that Joseph is affronted by Potiphar’s wife’s come on; you know, he’s so appalled that he’s having some sort of operatic hissy fit. But if you look at a shalshelet as denoting hesitation, or internal struggle, as the rabbis usually did, then I think it’s easy to read it as Joseph wavering between this tantalizing offer and turning her down. Rather than betray his master, Potiphar, who after all, has been good to Joseph, making him his chief attendant and head of the household, Joseph listens, maybe for the first time, to his better self, and says no.

He pays dearly for it, ending up in prison, where he goes from telling his dreams to interpreting them. From a literary standpoint, you can’t have Josephs’ success that follows without his complete fall. He has moved from favored son, into a pit, then slavery and now a prison. From the depths of prison we get not only a good story, but a way for Joseph to achieve redemption. What began with his being sold into slavery reaches its apotheosis. We no longer have a bratty tattler on our hands, but rather, a man who will interpret the dreams of Pharaoh and be taken seriously in the process. He will become a man who can command all of Egypt.

The shalshelet, in this case, denotes more than just personal hesitation and struggle. It’s a marker for a momentous turn in the story of our people. Joseph’s story is at its core, our story, one of the ups and downs of tragedy and success, that rises and falls just like the notes of the trope.

Good d’var! Not only do you leyn well, you teach well. As usual, I am so proud of you.