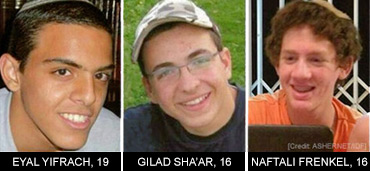

Their three faces, laid out in tiny mug shots across my Facebook feed, stare back, accompanied by the hashtag #BringBackOurBoys. Pray for them, hold a vigil, condemn their captors, bring them home.

Their three faces, laid out in tiny mug shots across my Facebook feed, stare back, accompanied by the hashtag #BringBackOurBoys. Pray for them, hold a vigil, condemn their captors, bring them home.

It is not the message, but their number that brings me up short. I see three faces and I am transported back to 2006. Three others were taken, two men, one boy, in separate incidents. It was another world. Facebook was mostly a college thing. Twitter had just launched. Social media did not remind me every hour that we were still waiting to hear…something. It could not rally us and make us passive, all at the same time.

Gilad Shalit came home in 2011. He spent five years in captivity after being kidnapped by Hamas militants. Udi Goldwasser and Eldad Regev came home, too. The returned to Israel in black boxes in 2008, mourned by all.

Neither is a fate we want for Naftali Frenkel, Gilad Shaar and Eyal Yifrach. But behind all the brave words and the intensive Israeli hunt for them through the West Bank, it is quietly what we fear.

Udi Goldwasser and Eldad Regev, reservists, were serving along the Lebanese border when Hezbollah launched rockets. In a cross-border raid, Hezbollah attacked their Humvee, taking the two men prisoner. Most people now believe they were dead when taken. But Karnit Goldwasser, Udi’s widow, campaigned tirelessly for her husband’s release, never once wavering in her public belief that they were alive. And never once forgetting to mention Ehud Goldwasser, or the much younger Shalit, who was taken. Their capture sparked the 2006 Lebanon War.

Shalit, was kidnapped separately a few weeks earlier on June 25, while doing his military service. Only 19 at the time, and became the face of a Jewish everyboy, skinny, bespectacled, a little geeky looking even in his army fatigues. His capture put a face on the danger of being an Israeli unlike anything else had in the 21st century. His absence spoke to what it meant to have a constant state of war beckoning almost daily.

But these three boys, #EyalGiladNaftali, as they are known across the Internet, were not soldiers. They were studying in yeshiva, and two were only 16. They were hitchhiking home on a Thursday, probably heading there for Shabbat, and never showed up. A frightening call, to Israel’s equivalent of 911, thought to be a prank, delayed a search for them. In our mobile phone, hyper-connected culture, it seems impossible that we could lose track of them.

Is there any connection between the boys taken now, and those stolen nearly a decade ago? Did the release of Gilad Shalit, and the trade for the remains of Udi Goldwasser and Eldad Regev for thousands of militant prisoners make the kidnapping of Frenkel, Shaar and Yifrach more likely? The thought comes to me and I push it away, not wanting to go there. Because we were obligated to bring back Gilad Shalit and the remains of Goldwasser and Regev. Weren’t we? Tradition, both Jewish and military, says you don’t leave your soldiers behind. Yet Gold Meir famously refused bargain with terrorists for the 11 Jewish athletes kidnapped at the Munich Olympics. The idea was that negotiating meant Jewish life would be cheap and at risk, anywhere and always. Maybe negotiating has been beside the point. It doesn’t seem like engaging in it or refraining from it has changed the outcome for Israelis.

As part of my job, I manage social media posts for the JCC Association, the organization where I work. As the first week of these boys’ captivity stretched on, I tweeted about praying for them. Someone with the Twitter handle @FriendlyAtheist wrote directly to me that, “praying does not make any difference.” And while I certainly wasn’t going to take to the Twittersphere and argue with him, I wondered, “Why is it that we pray? Do we really believe it will change the outcome?”

Certainly, some people do. And certainly a belief in prayer’s efficacy is embedded in our tradition. But perhaps prayer is more important to the person praying than to any deity. When we pray maybe it is we who change.

Even Naftali Frenkel’s mother, an Orthodox woman who teachers Jewish texts to other women, was quoted in the New York Times as saying, “I have a spiritual world, but it doesn’t lessen any pain and it doesn’t promise me anything because God doesn’t work for me. It’s not some kind of trick that if I pray hard enough, he’ll just show up.”

And still we pray. We pray that somehow these boys will come back. Because in a world where even as Jews we are fractured and at odds with one another, we need to unite. We need to believe. And we need to hope. We don’t want these boys’ disappearance to be a throwback to 2006, where waiting, and hoping, and yes, praying, seemed endless.

Five years of captivity is five too long. But the alternative scenario was worse.

Thanks for capturing so many of our thoughts so eloquently.