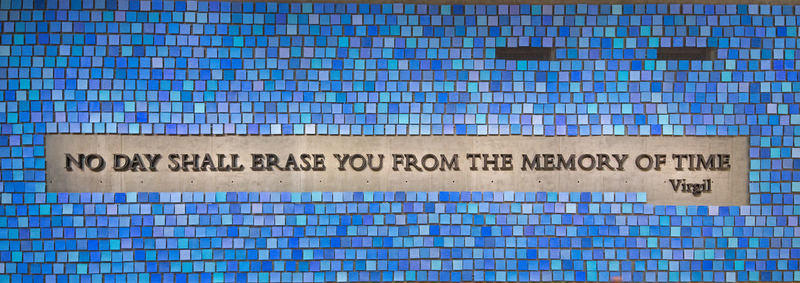

Artist Spencer Finch, “Trying To Remember the Color of the Sky on That September Morning,” at the National September 11 Memorial Museum

It doesn’t seem like much, a brush, a razor and a medium-sized manila envelope, given the weight of other items in the massive exhibit at the National September 11 Museum & Memorial that tells the story of that awful day. They are such quotidian items—the type of things you don’t think about, elevated to relic—in a small display case toward the end of this daunting exhibit.

They belonged to Joel Miller, who worked at Marsh & McLennan, in disaster recovery technology, of all things. Nine months after the Twin Towers came down, these items were used to identify his remains.

The first time I visited the museum, a few years ago, I don’t recall seeing these things. I was overwhelmed by the stories the museum so painstakingly has collected: of those who died; those who walked out alive; those who stayed home, or missed their train to work, or conversely were somewhere they usually never would be at the wrong time on that spectacularly bright and brittle Tuesday morning in September. The items are below my sight line and by the time I got to that point in the exhibit, I had wanted to leave.

Five years ago, I was able to tell Joel’s story in the newspaper I edited. His sister, Sondra Foner, shared it, and on this recent visit to the museum, it was those simple, daily belongings of a man I’ve never met, that spoke most eloquently about the enormous loss of that day.

We all remember that bluest sky and what we were doing 15 years ago when terrorists attacked our country. I was driving to the magazine I worked at in New Jersey, listening to the Beatles, loud. When I got to the office, our photo editor said a plane had flown into one of the towers. I noted it and felt bad, but went about starting my day, thinking like everyone, it was a small plane somehow off course in lower Manhattan.

We all remember that bluest sky and what we were doing 15 years ago when terrorists attacked our country. I was driving to the magazine I worked at in New Jersey, listening to the Beatles, loud. When I got to the office, our photo editor said a plane had flown into one of the towers. I noted it and felt bad, but went about starting my day, thinking like everyone, it was a small plane somehow off course in lower Manhattan.

“Another plane flew into the other tower,” she said.

“It’s a terror attack,” I said. What else could it be? Two times doesn’t happen by accident. And of course, before the day was out, we would learn the sheer size and evil genius of the plot, with planes hijacked to destroy the Pentagon and another that crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, foiled by passengers as it headed toward our nation’s Capitol.

I remained stuck at work throughout that day in the confusion of road closings and lack of phone connection. “People are going home in Indiana,” marveled a colleague’s husband on the phone. An ironworker, he had once walked the steel beams of the World Trade Center when it was under construction, and had, at least it seemed to me, the most personal connection to those buildings.

It seemed surreal we were still in the office. Who could concentrate? As a staff, we watched first one tower and then the other pancake in flame and dust on the television.

My husband was stuck in the city, my kids were safe in school in Rockland County, 23 miles north of Manhattan, but we were safe. Randomly emailing people, just to touch base, I reached out to my synagogue’s administrator.

“We are all crying here,” she wrote.

Yes, we were. Later in the day, I watched exhausted and dusty people stagger up 9W, walking home from the city on that main north/south road that runs in front of the magazine’s offices.

What is the legacy of that day? So many dead—nearly 3,000, including more than 400 fire fighters and police officers; two subsequent wars; one dead Osama bin Laden, who masterminded the attack; more attacks around the globe too numerous to list when you Google, “terrorist attacks since 9/11.”

We seem a little numb to it all. Terrorists coordinated suicide bombings and mass gunnings, killing at least 130 in Paris last November; Charlie Hebdo before it. A shooting rampage in San Bernardino, California and another in a gay bar in Orlando, Florida made headlines, along with the truck that ran through a crowd in Nice, France, while revelers celebrated Bastille Day. And those are just the ones I can recall easily. If I think a little harder, there’s the Jewish day school in Toulouse, the Jewish museum in Brussels, the mall in Tel Aviv, the ones that affect my own people. Who recalls the rest? Most far away, in Asian and Middle East countries, brutal and harsh, recurring more often than we realize.

The first time I visited the cratered sites of the Twin Towers after 9/11, was at my mother’s insistence when she visited. It was something I’d avoided doing. The idea of making a pilgrimage had seemed ghoulish at the time, but maybe that’s just the way we try to make sense of the senseless. It was again at her prodding that I went to the museum the first time, a few years ago.

During this visit, I realized that the transcript from the plane that crashed in Shanksville does not get any easier to read. The bravery of those who charged the cockpit seems generous, a small windfall of poignant beauty on a dark day. They understood they were going to die, accepted their fate and chose action. What is unfathomable are the words of the terrorists, insisting they drive the plane down, down, while shouting, “God is great.”

I walked out of this sequestered alcove dedicated to that part of the story, and thought, “Really? Is that the best your God can do?” I had to remind myself that the world is wide enough for both the terrorists and for U.S. Army Capt. Humayun Khan, also Muslim, who served us bravely, dying in a terror attack in Iraq, even as he warned others and saved lives.

There is another display that stood out this visit, a photo of a weary firefighter on a park bench. Firefighter Dan Potter had narrowly escaped death twice that morning, working through the collapse of both towers. The photo captures him on the bench in despair—he had just accepted that his wife, who worked on the 81st floor of the North Tower, had died.

There is another display that stood out this visit, a photo of a weary firefighter on a park bench. Firefighter Dan Potter had narrowly escaped death twice that morning, working through the collapse of both towers. The photo captures him on the bench in despair—he had just accepted that his wife, who worked on the 81st floor of the North Tower, had died.

Except that she hadn’t. She made it out alive. The picture, which captures Potter’s anguish, tells only that moment. Later that day, he found out that his wife had survived, and went to a fire station to volunteer to assist others.

Knowing the full story turns the photo from one of despair to one of hope. And it is probably why 15 years later, the one thing we recall so clearly from that day is that bluest sky.