JCC fall event to pay homage to slain athletes

Ankie Spitzer has an interview set up in the West Bank. Her assignment for Public Dutch TV is to get the reaction of Palestinian construction workers about Israel’s building freeze.

The workers don’t like it. The freeze means no work.

She’s standing on a hill studying the landscape. It’s more than 100 degrees. The light is harsh and the wind whips the sand and the rocks.

“I think, what am I doing here, why am I not at home?”

Home for Spitzer is Ramat HaSharon, just north of Tel Aviv. A native of the Netherlands,

Spitzer chose to make her home in Israel after her husband, Andrei Spitzer, along with 10 of his Israeli teammates, were murdered at the 1972 Munich Olympics by members of Black September, a Palestinian terrorist organization.

For those who remember, the image of one of the kidnappers, balaclava over his face, on the balcony of 31 Connollystrasse, where the Israeli apartments were in the Olympic Village, is indelible. For Jews everywhere, the events of Sept. 5, 1972 evoke fear and anger. For Spitzer, who has served as a representative of the families of the athletes who died, it has been a 38-year quest to keep their memory alive.

And Sunday, Nov. 6 at 8 p.m. she will be the guest of honor at JCC Rockland’s “Rock the Games.” The event, which will be held at the JCC, 450 West Nyack Rd, West Nyack, will be preceded by pre-event cocktail parties in private homes and will serve as the kickoff for the fundraising toward the organization’s hosting of the JCC Maccabi Games in 2012.

Those games, an Olympic-style sporting event that will bring more than 1,800 teens to Rockland, have been dedicated to the memory of the “Munich 11,” those athletes who were taken hostage and murdered after 20 hours of failed negotiations and a botched rescue attempt on the part of the German government.

The 1972 Israeli Olympic team photographed just before they left for Munich. The 11 team members taken hostage and later killed are numbered.

While all JCC Maccabi Games have a component of remembering the Munich 11, JCC Rockland has dedicated their games to the memory of the athletes. The event honors each athlete and local community leaders — such as JCC Maccabi leaders, government officials, educational institutions, and business groups, among other individuals and institutions [including this newspaper] — that have a role in bringing the games to Rockland. They will stand in for the athletes at the event.

The event is the first — with 11 more to follow — over the next 21 months where the torch, which will be used when the games open at Michie Stadium at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, will be passed along the way. Spitzer will lead the torch lighting ceremony on Nov. 6 along with the other honorees.

During the lead up to the games, teens in the county will participate in Change4Change, a coin collection project that aims to collect 11 million coins, one million for each of the 11 slain athletes. It’s an enormous undertaking, and Spitzer recognizes that.

“First this came to Anouk,” her daughter by Andrei, who received a request to participate in the events from JCC Rockland CEO David Kirschtel. “We were amazed at the originality, the drive and the willingness to do all this for the memory of my husband, her father and the other guys,” Spitzer said. “I’m telling you, only in American can they do something like this. In Israel, people remember and they remember it very well with all kinds of memorials and statues and places and sports stadiums and whatever, but I don’t think anyone would ever go through this, to make such a project in memory of the 11.”

For Kirschtel, it was a way to give real meaning to the games the JCC will host. With the 2012 games leading a capital campaign [see related story] to raise funds for the Rockland Jewish Community Campus, and the coin project helping to drive sponsorships, remembering the athletes would, in his eyes, imbue the entire enterprise with real meaning.

“This isn’t just another JCC fall event,” he said of Rock the Games and all that entails. “We needed to do something with meaning, something important and that says something about who we are as a community. I can’t think of any better way of doing that.”

OUR WORST FEARS

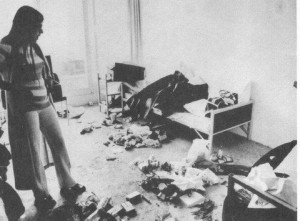

Ankie Spitzer surveys the room where her husband, Andrei, and his teammates were held before they were murdered.

On Sept. 5, 1972 around 4 a.m. a small group of men scaled the fence of the Olympic Village in Munich, Germany. Throwing their sports bags over the fence, they looked like athletes returning home late, reluctant to face security. German officials, hoping to vanquish Germany’s authoritarian image, had tried to create an open and relaxed environment with little security.

In retrospect, it was easy for members of the little-known Palestinian terrorist group Black September, to break into the Israeli apartments at 31 Connollystrasse in the village. Inside, Yossef Gutfreund, an Israeli wrestling referee awoke when he heard the noise.

Checking out the situation and finding armed men at the door, he threw his 6-foot-3-inch, 290-pound frame against the door, barring the terrorists’ entry for a few crucial seconds, allowing one of the Israelis to escape through a window.

As a terrorist burst into another apartment, they were surprised by Moshe Weinberg, a wrestling coach, who had grabbed a knife. They shot him in the cheek.

In addition to Gutfreund and Weinberg, the terrorists took Andrei Spitzer, fencing coach, Amitzur Shapira, athletics coach, Kehat Shorr, marksman coach, Yakov Springer, weightlifting judge, David Berger, weightlifter, Ze’ev Friedman, weightlifter, Eliezer Halfin, wrestler, Yossef Romano, weightlifter, and Mark Slavin, wrestler.

One of the athletes, Gad Tsobari, was able to escape. In the chaos, Weinberg was killed.

As their captors pushed the athletes into the room, Yossef Romano disarmed one of his captors, only to be machine-gunned to death.

The terrorist demanded the release of more than 230 prisoners from Israeli jails. After 20 hours of negotiations with German officials, they were granted passage to Egypt. The Germans provided two helicopters to take them to Fürstenfeldbruck, an airfield about 12 miles outside of Munich. There a Boeing jet would be waiting to transport the hostages and their eight captors.

Snipers had been placed at the airfield, but the German rescue attempt was poorly planned with too few sharpshooters, not enough light and no walkie-talkies. An “air crew” of police bailed out of the plane at the last minute. A two-hour gun battle ensued. All the athletes and five of their captors were killed. Three terrorists were caught, but later returned to Arab countries during what is suspected of being a sham hijacking arranged by the German government.

Although there had been previous Palestinian terrorist actions, such as the 1968 hijacking of an El Al flight from Rome, nothing had rivaled the scope and spectacle of the Munich attack, according to Brigitte Nacos, a journalist and adjunct professor in Columbia University’s political science department.

“It was a very different media landscape then,” says Nacos, author of “Mass-Mediated Terrorism: The Central Role of the Media in Terrorism and Counterterrorism.”

“They did something that from their point of view was very clever. By doing this at the Olympics, you had the international media present….They were assured hundreds of millions of people would see this, and that’s what they got.”

TO REMEMBER

Ankie Spitzer surveys the room where her husband, Andrei, and his teammates were held before they were murdered.

Ankie Spitzer was only 26 when she traveled to the Olympics with Andrei, her husband of only 15 months. They had met in Holland, where Andrei was her fencing coach. They left their two-month-old daughter Anouk in Holland with family. Andrei, in particular, was filled with the excitement and hope of what the games meant: to compete without borders, in an atmosphere dedicated to the sportsmanship and international goodwill.

After the massacre, Spitzer insisted on seeing the room where the Israelis had been held captive. It was in shambles, strewn with filth, blood and rubble. Bullet holes pocked the walls.

“This is where Andrei spent the last days of his life, in this incredible chaos, where he was sitting with the other guys, bound hands and feet to a bedpost, looking at his teammate dying slowly in front of him,” she says of that day. “If this is what happened here, in the Olympic Village, then I will not shut up. I will continue to tell this story.”

Spitzer made that vow, and has kept it, dogging the International Olympic Committee and its president for a moment of silence during the opening ceremony to commemorate the athletes. While there is always a memorial during the games, it is offsite and not connected to the games themselves. The answer from the IOC is that to do so would be a political act.

Spitzer retorts that you can eliminate mentioning that the murdered men were Israelis. If the Arab delegations walk, so what?

“What do I care about the Arab delegations if they don’t understand the idea of the Olympics?” she answers. “You have 10,000 athletes in front of you,” she says. “Tell them the message so they will understand what happened and so that it will not happen again.”

JCC Rockland CEO David Kirschtel, right, and JCC Maccabi Games Director Eric Lightman check out Michie Stadium at West Point.

The JCC Association has tried to address the issue in its own way, by incorporating the athletes into the JCC Maccabi Games each year. Kirschtel believes that by bringing

Spitzer here, and making the Munich 11 a cornerstone to the games, the attention may help redress this imbalance.

“These men came to participate in international games dedicated to goodwill, fair play and excellence,” says Kirschtel. “They came home in coffins. The world should never forget that.”

Already Rep. Eliot Engel (D-NY), whose Rockland offices are less than a half-mile from the JCC on West Nyack Road, has agreed to introduce a resolution during the next Congress to support a moment of silence during the Olympics, which will take place in London in 2012, only weeks before the JCC Maccabi games are held in Rockland.

Engel remembers watching the Olympics, seeing the events unfold on the news. That there’s been no attempt to remember the athletes in the context of the games angers him.

“It’s outrageous that the International Olympic Committee has never held a moment of silence or commemoration for the Israeli athletes,” says Engel, who feels he’ll easily find bipartisan support for the measure. “So maybe we can shame them a little.”

Spitzer arrives in Rockland on Monday, Nov. 1 following a press conference the day before at Kfar Maccabiah, a conference center in Israel that will be simulcast along with one at JCC Rockland. At that time, the JCC will launch the Change4Change project.

Spitzer’s week here is a whirlwind of appearances. She will mostly address students, speaking at six different schools while she’s here. But she will also address business and civic groups as well about the Munich 11.

For Clarkstown Central School District Superintendent Meg Keller-Cogan, Spitzer’s speaking to three high schools and three middle schools in the county, including Clarkstown High School North on Nov. 5, is a way to bring those events into focus for the students.

“I’m really honored by her visit,” said Keller-Cogan, who was a young students at the time of the ’72 Olympics and remembers ABC broadcaster Jim McKay announcing, “They’re all gone.” As schools have coped with increasing anti-Semitism, gay bashing and other acts of intolerance, she’s hoping a visit like Spitzer’s will spark discussion and help educate the students about where acts of hatred can lead.

“I’m hoping our students will gain an understanding of what a human rights violation this represents,” she said of Spitzer’s visit. “It’s an important part of world history.”

One appearance Spitzer will make will be to discuss the events with the very 10th and 11th graders who will be leading the county in collecting coins in memory of the athletes.

The meeting for “Changemakers,” as they’ve been dubbed, is open to any high school students who wishes to hear Spitzer speak and will take place on Thursday, Nov. 4. at 7:30 p.m. at the JCC, 450 West Nyack Rd., West Nyack.

Spitzer has gone on to raise Anouk and three other children from a second marriage, Kim, Arbel and Carmel, in Israel. She felt in Israel, Anouk would not stand out as a fatherless child, with other classmates around who had lost parents in war. She has had a long, successful career in television, working for the Dutch program, “Nieuwsuur” (Newshour) and as a Middle East correspondent for Belgian National TV, interviewing along the way, the likes of Yasser Arafat, the head of the Palestinian Liberation Organization and Abu Mazen, president of the Palestinian Authority.

She has never shied from the controversial, and plans on pursuing her goal of a moment of silence forever.

“I will not stop,” she says. “And when I am tired and then dead, my kids will come. This is what should be done, the minimum. This is what you owe them.”

There are all sorts of events that Spitzer says she’s invited to participate in throughout the world regarding the athletes that she takes a pass on. Being part of the JCC’s memorial was one she felt worth doing. Through the JCC Maccabi Games, the teens participate, learn and come together despite differences. It was the same thing she once felt the Olympics represented.

“I’m hoping the kids will get something educational out of it,” she says. “They should use sports as a means to get close to one another and understand each other better. That is my mission. It’s a big word but that is what I want to do.

“I feel I owe it to these guys.”