Last Father’s Day I had a dad. This Father’s Day, I have memories. And I’ve been sorting through them ever since he died in January.

My husband warned me that in morning minyan they might ask me to share some thoughts about my dad. Fortunately, this only happens on the yahrtzeit, which is seven months away. Nonetheless, I came up with a story right away.

“When I was about four, he took me shopping for a coat. When we went into the store, I saw this stuffed toy – it was a horse with red, yellow and blue polka dots on it. The horse was high up on a shelf. I really wanted it. He said I could have it, if I could get it.”

I remember wondering how I was going to reach the horse. He put me on his shoulders. I can still recall stretching my arms toward it, unable to grasp the toy. It was just out of reach, so close I thought I should be able to get it, and that I simply wasn’t trying hard enough. My father put me down and we bought a coat and left. I don’t remember if I cried on the way home, but once I got there, I was inconsolable. In my memory, he brought me the horse a few days later, but my mother says he went back that afternoon.

My husband gave me a look. “You can’t share that.”

“Why not?”

“Because it’s awful. How could he do that to you? You were a little kid!”

I had to think about it. How could he? I don’t’ know. That’s just how he was. My father was a terse man who shared little and answered less. I’m guessing that he felt if I really wanted something, I ought to work at it. The memory is bright and clear, like a piece of glass. I still have that stuffed horse. I keep it on a high shelf in my bedroom closet. He’s a bit worse for wear, but he got that way from being well loved.

I also remember, just as clearly, going to a ballgame, the whole family. It had to be 105 degrees in Arlington Stadium and we were going to root, root, root, not for the home team, the Texas Rangers, but for the Boston Red Sox!

My dad was born in Brookline, Mass. and though his childhood there was plagued with money woes, moves and evictions and friction with his own father, he had a fierce nostalgia for the place. He loved Brigham’s ice cream with jimmies – not sprinkles -fried clams with the bellies, chocolate NECCO wafers, and of course, the Red Sox.

So there we were, the only Red Sox fans in a sea of rednecks, all cheering for the Rangers. The man in front of us was completely sizzled, but his support wasn’t unequivocal, though. Whenever the Ranger’s right fielder, Claudell Washington came to bat, he’d sneer, “C’mon Claw-dell, you kin hit it!”

There was an incipient racism stuck in the guy’s throat. The sour beer smell that emanated from him along with his slightly veiled prejudice still mingle unpleasantly with the Red Sox loss that day. How could they let the awful Texas Rangers win? We left the stadium, hot, sweaty and defeated.

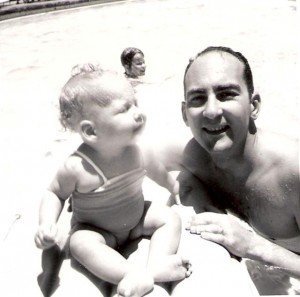

When I was little, my father was away a lot. He traveled as a sales representative for a women’s clothing line, crisscrossing the state of Texas by car to show his wares at what were then family-owned department stores. The summer I was between second and third grade he took me with him. We stayed at Roadway Inns at night and drove long, flat Texas roads by day. We’d show up at a store and they’d take my dad to a room in back, where he’d wheel in the clothing rack loaded with dresses and pantsuits bundled together in enormous black garment bags tied around the middle. My dad would undo the bags and ease the creases from the clothes with a standup steamer, its sinister black hose and nozzle capable of the worst sorts of burns if you got in the way. I’d sit quietly on the floor, playing with the plastic clothing clips that had fallen there.

In San Antonio, the department store was down the block from the Alamo. He showed me the store and then left me at the Alamo, where I took in the historic exhibits. When I was done, I walked alone to the department store. I don’t remember how I found my father; he must have given me the name of someone to ask for. I can’t imagine allowing a child that young to wander a strange city alone. But looking back at it, I feel a certain sense of pride in my eight-year-old self for not panicking, for not getting lost.

When I left for college in New York, my dad gave me the most useful gift he could think of, a tape gun. I still have it. It has a large reel for tape and a jagged edge for cutting, the sort of thing that people who pack and ship things for a living own. My dad was always on the move before he met my mom and settled down. As a kid, he would run away from home, ending up with his aunt and uncle when things got bad at home. He left Brookline young and lived in North Carolina before arriving in Houston. When he married, my parents moved to Dallas. I’ve also done my share of moving. Eventually I ended up in New City, where I’ve been for almost 10 years. The only place I’ve lived in longer is my hometown, Dallas. So my dad figured it right, that a tape gun would come handy.

Over the years I gave my father gifts as well, a lot of Red Sox paraphernalia; the sorts of papier mache things you make in school for Father’s Day; and a silver ring with an enamel design that I made when I worked as a jeweler.

I know he was proud of me, and I know that he loved me. Sometimes it was really hard to tell. But the day he died, he was still wearing the ring I had made.

This Pesach I attended the yizkor service for the first time. I’ve always scooted out before, perhaps afraid of invoking the ayin hara, or evil eye, on living parents. The yizkor prayer spoke plainly to me: May I prove myself worthy of the gift of life and the many other gifts with which he blessed me.

Through minyan and these months of mourning, I have been trying to figure out just what it is my father gave me. He had a difficult relationship with being Jewish. He didn’t like ritual, observance or things you were “supposed” to do. In this respect, I am very unlike him, taking on more observance as I’ve aged.

At the same time, he saw himself as Jewish and wanted to be seen as such by the most devout, often approaching Hasidim in the local supermarket to chat with them and their children. “I’m Shmuel,” he’d say, giving the Hebrew name that he never used.

He didn’t put up with much nonsense from anybody, and he wasn’t very patient. These things, I know, he bequeathed to me. He taught me that the things you really want, you have to work at. That you should always root for the underdog. Self-sufficiency is paramount. Don’t ask for help unless you really need it and no one can take advantage of you unless you let them.

And as any good Jew knows, you should always be prepared to pack quickly (and in our case, professionally). He also knew that there wasn’t anything that dark chocolate couldn’t fix, or at least make better, and that it’s really hard to feel bad if you sing something by Gershwin or Rogers and Hart (in his case, off-key and loudly).

These are the gifts my father left me. They have served as guides throughout my life. And maybe that is the most you can ask for from a parent.

Last Father’s Day I had a dad. This Father’s Day, I will miss him.