A Jewish boy comes home from school and tells his mother that he’s been cast in the school play. “That’s wonderful. What part do you have?” she asks.

The boy says, “I’m playing the part of the Jewish husband!”

The mother scowls and says, “Go back and tell the teacher you want a speaking part.”

And there you have it in a nutshell, the Jewish mother stereotype. She’s overbearing. She’s already micromanaging her young son’s life. And she dominates her husband. The only thing missing in this succinct little portrait is the mom who nags her daughter about when she’s going to give her grandchildren.

For better or worse, we’re stuck with the Jewish mother joke. And like most stereotypes that sting, there’s probably a little truth buried in it. One need look no further than the core of our tradition to find ample evidence that Jewish women, have from the moment that there’ve been Jewish women, worked behind the scenes and made us into the people we are today. Just open up the book of Bereshit and it’s all there.

Sara, unhappy with how her husband, Abraham’s older child is playing with their young son, Isaac, demands that Abraham send the boy, Ishmael and his mother, Hagar, away. Out in the desert, Hagar wails at her fate. God promises her that her son, too, will father a great nation.

Just think what might have happened if they’d all attended family counseling instead? We might never have gotten the chance – or even come into being, for that matter – to meet the über-Jewish mom of them all, Rebecca.

Troubled during her pregnancy, Rebecca cries to God, who informs her that two children struggle in her womb and they will become two nations, the younger the mightier of the two. Rebecca does not take this message lightly. Years later it has become clear that the first born, Esau, is his father, Isaac’s favorite. Rebecca however, favors her younger son, Jacob. Rebecca has Jacob disguise himself as his brother and usurp his father’s blessing for the first-born.

And there’s your blueprint for the Jewish mom of the jokes, pushy, meddling in her sons’ lives, dismissive of her spouse. Sounds pretty bad, right? Except where would the Jewish people be if Rebecca hadn’t promoted the younger son over the older one? Would we have become the Children of Esau instead? Or would we be just be a footnote in the Torah?. Rebecca might have been manipulative, but she was shrewd and tough, and doing God’s bidding if you get right down to it.

But I don’t want to make light of Torah, equating it with one long Jewish mother joke. I’m only suggesting that maybe we’re looking at this all wrong. We’ve taken some rather emphatic traits among our imahot – strong, willful, smart and farsighted – and turned them upside down and inside out so that they become negative instead, the punch line of many a joke.

Look at the Eshet Chayil, the song that the Jewish husband sings to his wife before the Shabbat meal each week. Extolling the “woman of valor” the song describes this unstoppable being who far exceeds expectation at every turn.

Strength and splendor are her clothing, and smilingly [she awaits her] last day. Her mouth she opens with wisdom, and the teaching of kindness is on her tongue.

The poem likens her to merchant ships, to someone who can plant vineyards, turn fiber into cloth and be an active participant in public affairs, all on her family’s behalf. And when she’s not busy being supermom and superwife for her own family, she’s off performing acts of tzedakah on behalf of the poor. Whew! I’m tired just thinking about her.

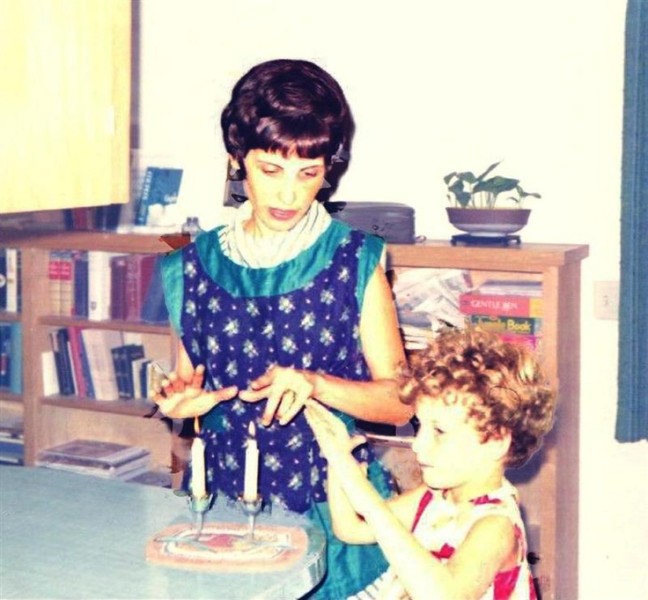

For many of us, our first Jewish memories are connected intimately to the smells and tastes of holidays. Our mothers saw to that. Well, certainly, my mother did. My own upbringing didn’t involve rigorous observance or regular shul going. But I still felt very Jewish, and I think it was through the active preparation for each holiday with my mom, from lighting the Shabbat candles, to painstakingly rolling out hamentashen dough and filling them with poppy seeds each Purim, to flipping the latkes in the bubbling oil that helped create that special sense that being Jewish was a really terrific thing to be.

While I was growing up, I remember my mom being involved in Hadassah and Sisterhood and to this day, she continues to impress me with her Jewish commitment. She’s actively involved in her synagogue, serving on the buildings and grounds committee, volunteering at the annual summer film festival, and regularly attending Shabbat services. She has been taking a Hebrew class for several years and she belongs to a monthly Jewish book group. With my father, she has been part of a vibrant Havurah for more than 20 years. Recently she was elected vice president of her Sisterhood chapter and was able to attend Women of Reform Judaism’s annual leadership conference in Washington D.C. Whew! I’m tired just thinking about her.

My mom is not alone. I see women like her at my shul and know of others through work and my children’s school. They are the backbones of our Jewish volunteer groups. They come to shul to make food for shiva houses and send mishloach manot home with our children. When they get some time for themselves (Time? What’s that?) they take Ulpan and Melton classes because they feel like they need to know more.

So whether your mom made the best brisket in the world, schlepped that unruly carpool of your friends to Hebrew school every Monday and Wednesday, sang the Sh’ma to you each night, or made you attend rallies for the Soviet refusniks, she was molding your Jewish persona from the very start. She might have seemed bossy, overbearing, forceful and maybe even nudgey, like the jokes make her out to be. But where would you be without her? Think of her instead as a force to be reckoned with.

And her worth is that above rubies. Happy Mother’s Day.

May 2007

loved loved loved this piece! Happy Mothers day!